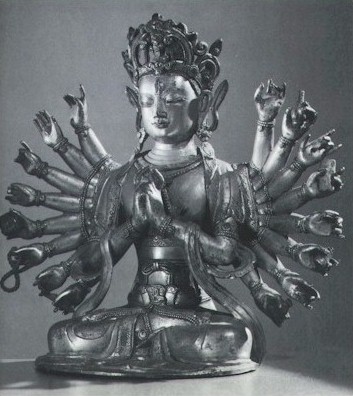

In Jack Kerouac's novel Dharma Bums the protagonist, alter-ego of Kerouac, named Ray Smith, encounters 'the number one Dharma Bum of them all', Japhy Ryder, who instantly decides that Ray is a great Buddhist sage, possibly a reincarnation of Avalokitesvara, the Great Compassion Bodhisattva (more likely, though, a reincarnation of Goat or Mudface, Ryder teases Smith later on), and when they enter a San Francisco bar together and their friends inquire where they have met, Ryder gleefully announces: "I always meet my Bodhisattvas in the street!"

In Jack Kerouac's novel Dharma Bums the protagonist, alter-ego of Kerouac, named Ray Smith, encounters 'the number one Dharma Bum of them all', Japhy Ryder, who instantly decides that Ray is a great Buddhist sage, possibly a reincarnation of Avalokitesvara, the Great Compassion Bodhisattva (more likely, though, a reincarnation of Goat or Mudface, Ryder teases Smith later on), and when they enter a San Francisco bar together and their friends inquire where they have met, Ryder gleefully announces: "I always meet my Bodhisattvas in the street!"

This sets the tone for the whole novel, which is perhaps even more celebratory of its culture hero than On the Road was in its beatification of Neal Cassady, alias Dean Moriarty. The two protagonists share a relationship of mutual respect and growth - again with Smith as the more passive learner and Ryder as the master woodsman, wilderness survivor, mountain climber, haiku improviser, Zen riddler and seducer of young women into the practice of yabyum (Tantric sex...)

Ryder's real life model was of course Gary Snyder, the great Zen practitioner among the Beats - a poet who was also a student and scholar of oriental languages and texts, and later among the first poets instrumental in writing from a non-anthropocentric point of view, expressing a deep-ecology ethos and an eco-critical practise. Snyder has often warned that people should not take everything in Dharma Bums as complete truth, but he does acknowledge that Kerouac's description of his lifestyle is correct in most respects.

In the course of the novel Kerouac paints a very sympathetic portrait of Ryder, and unlike Moriarty in On the Road, this new Buddhist culture hero does not end up betraying the protagonist. Rather it is the Ray Smith figure who at the end abstains from following the hard path to enlightenment that Ryder has helped him embark on, and he decides to literally come down from the pinnacles after a season as a fire lookout on Mount Sourdough's Desolation Peak and once more rejoin the human community with all its temptations of the flesh. Still Smith misses Ryder who has gone off to Japan to live in a monastery and realizes what a strong, serious scholar Ryder will become.

Again, there are clear parallels between the novel and the real life of Gary Snyder. Snyder was born in San Francisco, but his family moved to the Pacific Northwest, where Snyder's father began working in the logging industry. Snyder developed a love of the land from an early age on, and acquired forest and mountain craft through interacting with his environment. He studied anthropology in Portland at Reed College and left there with a BA in 1951. Later he pursued graduate studies at Berkeley, switching from anthropology to Oriental languages, to further his understanding of both Oriental poetry and Buddhist scriptures. Snyder has written a mini-autobiography for Modern Haiku and in there he begins:

This mixture of manual and intellectual pursuits came to mark Snyder's outlook in profound ways and is also one of the reasons behind the frequent comparison with Henry David Thoreau:I was from a proud, somewhat educated farming and working family. After finishing college I went back to work. I went into the National Forests to be an isolated fire lookout living in a tiny cabin on the top of a peak. I worked as a summertime firefighter and wilderness ranger, and then spent winters in San Francisco to be closer to a community of writers.

This and Snyder's riposte to the Thoreau comparison, along with a great number of other Snyder quotes can be found here. Whereas Thoreau had his Walden Pond, Snyder had his Pacific Northwest - an altogether more rugged and demanding terrain. Already from Snyder's first collection of poetry, the sense of place was one of the most striking features of his poems. His programmatic meta-poem "Riprap" (the title poem of that collection) perfectly illustrates the fusion of poetical practice and hard manual labour. The poem can be found in its entirety on-line here and here. The speaker's absolute certainty of the equal value of building a path up a mountain and composing a poem never ceases to amaze me: each stone and each word matters equally, and the "Solidity of bark, leaf or wall/riprap of things" leads straight out onto the "Cobble of milky way/straying planets" putting us in our place in the Cosmos (this line echoes with Ginsberg's "ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo [...] of night", but has no urban angst built into it). Snyder then draws us inward: "In the thin loam, each rock a word/a creek-washed stone/Granite: ingrained/with torment of fire and weight/Crystal and sediment linked hot/all change, in thoughts,/As well as things" - reminding us of the connection between thought and matter and the fiery origins of both. Fire is, in fact, Snyder's favourite element of change, signalling as much rebirth and life as destruction."If Ginsberg is the Beat movement's Walt Whitman, Gary Snyder is the Henry David Thoreau. "-- Bruce Cook

The other half of the first Snyder collection was made up of his translations of the Cold Mountain poems by Han Shan, a 9th century Chinese hermit poet, who took his name after the place in which he lived. Snyder's congenial translations indicate the strong identification between the young aspiring poet and the old master. Here is Snyder's translation of "Clambering up the Cold Mountain Path". The poem ends with a question reminiscent of a koan, or Zen riddle: "Who can leap the world's ties/And sit with me among the white clouds?" No doubt this reflects what Snyder desired to do...

Snyder describes his years in Japan in the following terms:

The practice of haiku was already introduced to the American readers by scholarly translations of Basho and other masters of the form, but a much more efficient boost of cultural transfer was performed by the characters of Dharma Bums who trade off spontaneous haikus during a climb of Mount Matterhorn in California like a couple of jazz-men trading riffs and licks. Smith teaches Japhy to be spontaneous, Japhy teaches Ray the discipline of mind required for the haiku to have an enlightening effect. Kerouac has published many of these so-called western haikus (they don't conform to the syllable structure (3 lines of 5-7-5 syllables, respectively) that Japanese haiku poetry always follows) in books such as Pomes All Sizes, Scattered Poems and Some of the Dharma. Read more about Kerouac's western haiku practice on this page.I first arrived in Japan in May of 1956. Exposure to Buddhist scholars and translators soon brought me to the Zenrinkushû, that remarkable anthology of bits and pieces of Chinese poetry plus a number of folk proverbs as they became used within the Zen world as part of the training dialog. If one was looking at the possibilities of “short poems” the Zenrinkushû practice of breaking up Chinese poems would certainly have to be included. R.H. Blyth famously said “The Zenrinkushû is Chinese poetry on its way to becoming haiku.” Maybe it is that somebody — one of the old Zen monk editors — realized that practically all poems are too long and that they’d be better if they were cut up. So he cut up hundreds of Chinese poems and came out with new, shorter poems! I now know I was extremely fortunate to have been exposed to the elegant “Zen culture” aspects of Kyoto. But as I traveled around Japan I came to thoroughly appreciate popular culture, ordinary people’s lives, and the brave irreverent progressive vitality of postwar Japanese life. I realized that the spirit of haiku comes as much from that daily-life spirit as it does from “high culture” — and still, haiku is totally refined.

Before going to Japan, Snyder had also been hitchhiking extensively up and down the West Coast, sometimes accompanied by Ginsberg, who had become friends with him after both men had participated in the legendary Six Gallery reading in late 1955. Here is a recent interview where Snyder recalls their reading at Reed College - a tape of which, containing the earliest known reading of "Howl", has just surfaced.

Snyder had also spent several summers working as a fire lookout for the Forest Service. He recommended Kerouac for the job, and the summer of Snyder's leaving for Japan, Kerouac manned the small look-out cabin on Sourdough Mountain in the North Cascades. An excellent volume commemorating the stays of Snyder, Kerouac and Philip Whalen on Sourdough has been produced by the very same person who unearthed the "Howl"-tape, John Suiter. His Poets on the Peaks site has sublime photography showing us the things these young men may have seen in the 1950s summers they spent up there in splendid and sometimes terrifying isolation. Kerouac wrote about this experience in two novels, Dharma Bums (somewhat romanticized) and Desolation Angels (with more of an emphasis on the terrors of the void)...

I think Snyder's work as a fire lookout was directly instrumental in his choosing Smokey the Bear as yet another avatar of the Great Sun Buddha. In what is the funniest Snyder poem I have ever read, "Smokey the Bear Sutra", the friendly figure known to every child in America becomes both holy, sublime and hilarious in the best "Zen Lunatic" tradition. You can read the poem here (although Snyder graciously allows us all to "reproduce it free forever", it is a bit long to quote in full here...)

Suffice it to say that Snyder lets his readers participate in a hitherto unheard of non-human centered audience given as "a Discourse to all the assembled elements and energies: to the standing beings, the walking beings, the flying beings, and the sitting beings -- even grasses, to the number of thirteen billion, each one born from a seed, assembled there." This message is about the Future of Turtle Island (perhaps better known to the white man as America), where trouble is brewing: "The human race in that era will get into troubles all over its head, and practically wreck everything in spite of its own strong intelligent Buddha-nature..." Only the figure of Smokey will emerge to put out the uncontrollable wildfires and other destructions that mankind has unleashed on the earth:

With a halo of smoke and flame behind, the forest fires of the kali-yuga, fires caused by the stupidity of those who think things can be gained and lost whereas in truth all is contained vast and free in the Blue Sky and Green Earth of One Mind; Round-bellied to show his kind nature and that the great earth has food enough for everyone who loves her and trusts her; Trampling underfoot wasteful freeways and needless suburbs; smashing the worms of capitalism and totalitarianism; Indicating the Task: his followers, becoming free of cars, houses, canned foods, universities, and shoes; master the Three Mysteries of their own Body, Speech, and Mind; and fearlessly chop down the rotten trees and prune out the sick limbs of this country America and then burn the leftover trash.

This figure of trust and ancient wisdom - but also the bearer of a cleansing fire - will herald a new age for "Those who love woods and rivers, Gods and animals, hobos and madmen, prisoners and sick people, musicians, playful women, and hopeful children", who, chanting Smokey's mantra: "DROWN THEIR BUTTS - CRUSH THEIR BUTTS", will make the world safe, so we will all have "ripe blackberries to eat and a sunny spot under a pine tree to sit at. AND IN THE END WILL WIN HIGHEST PERFECT ENLIGHTENMENT." Amen!

With this radical turn into eco-critical poetry the mature Snyder tone is established. In my session this week I spoke about Snyder's poetics and its heritage from Transcendentalism and the American Romantic age, esp. in its belief in a chain of beings and a transmission of the divine through all beings, the poet being but a conduit. You can learn more from my agenda for analysis for Snyder which suggests his techniques, themes and some contexts for his work.

In my session I also suggested that Snyder was a catalyst for the meeting of East Coast Beats and West Coast poets (often discussed as the San Francisco Renaissance), but more than that he helped seed the central Beat figures with a more Orientalist outlook, turning them on to Buddhist beliefs and ancient poetry of the East, and furthermore I see him as setting Ginsberg on the course that made him a lynch-pin between the Beat Generation and the 1960s multifaceted Counterculture - a movement Snyder also enthusiastically joined upon returning to the US in the late 60s.

I want to close with a clip from one of the few documentary films on Snyder. It can be found in four instalments on YouTube. Here I embed the first bit and after that you'll see links to the other three...

Episodes 2, 3, and 4

Here is the Gary Snyder Reader: Prose, Poetry and Translations 1952 - 1998 which will give you 600 pages of poetry, essays, interviews etc. to peruse... It contains good selections of poetry from Regarding Wave, Turtle Island, Axe Handles, and Mountains and Rivers Without End, as well as prose from Earth House Hold, A Place in Space, The Real Work and The Practice of the Wild.

Snyder is also well represented in the Buddhist Beat reader, Big Sky Mind: Buddhism and the Beat Generation, ed. by Carole Tonkinson (out of print, but available second-hand)

Here is a more recent picture of Gary Snyder:

Snyder is very much still with us, dwelling among the species that surround us. His most recent book of essays came out in paperback a month ago: Back on the Fire. Most recent poetry collection was Danger on Peaks (2004).

Long may he remind us of our place in space!

View of Hozomeen Peak from Desolation